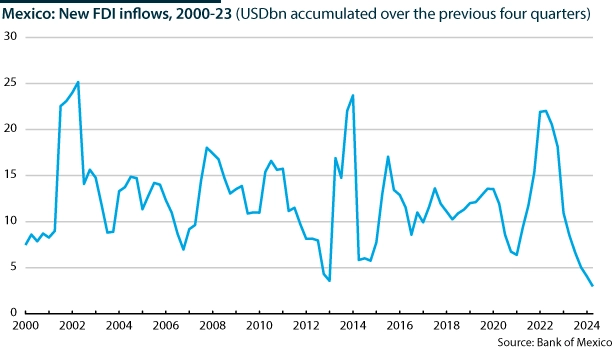

Fresh foreign investment has plummeted in Mexico this year, against a backdrop of anticipation of major reforms

The government published its judicial reform in the Official Gazette of the Federation on September 15. The overhaul has long been a stated goal of President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO), who claims it will reduce corruption and make judicial personnel accountable to the people. Critics say it ends the judiciary’s political independence and leaves it more vulnerable to manipulation. Concern around AMLO’s reforms appears to have coincided with a marked drop in investor confidence in Mexico.

What next

The task of implementing the reforms passed this month will fall to President-elect Claudia Sheinbaum, who takes office on October 1. She has publicly supported AMLO’s reform agenda, but at least some of the proposals being pursued are likely to have a seriously detrimental effect on Mexico’s investment environment. It is unclear how much influence AMLO will retain after leaving office, but Sheinbaum’s promise to maintain his legacy suggests it will be significant.

Subsidiary Impacts

- A depreciated peso would normally encourage foreign investment, but uncertainty may outweigh that potential benefit.

- The weaker peso may encourage Mexicans abroad to send more remittances home, partly compensating for lower FDI inflows.

- A hastily implemented constitutional overhaul could generate tension with the new US administration that takes office in January.

Analysis

Bank of Mexico figures for the country put the value of total foreign direct investment (FDI) — including new FDI, reinvested profits and transfers between companies belonging to the same group — during the second quarter of 2024 at USD5.1bn. That is the lowest second-quarter level recorded since 2004 and the lowest amount in real terms since 1996. The total accumulated during the previous four quarters was USD35.3bn, within the USD33-38bn range generally recorded in recent years.

USD5.1bn

Total FDI in Mexico in the second quarter of 2024

AMLO often claims that FDI inflows during his presidency have been greater than under any previous president. That claim is questionable — FDI under AMLO sat at USD200.0bn as of June 2024, slightly below the USD203.5bn recorded under former President Enrique Pena Nieto (2012-18) up to June 2018. Moreover, in real terms, FDI under AMLO is significantly below that achieved under the administrations of Pena Nieto and former President Vicente Fox (2000-06).

FDI levels under AMLO also compare fairly poorly with amounts recorded by similar emerging economies such as Brazil. As a proportion of worldwide FDI, the last time that of Mexico was more than 3% of the total was in 2013; it has not received more than 4% since 2002.

Damaging investor confidence

FDI during the AMLO administration might have been appreciably higher had the president not attacked private investments in energy. Private investment in the oil sector, both foreign and domestic, stopped almost completely when AMLO took office, with only projects already underway at the beginning of his presidency allowed to continue. The Spanish multinational Iberdrola was pushed into selling several of its electricity generators to the government.

The AMLO administration established state-owned enterprises to participate in several sectors, including mining and transportation, and sought to strengthen considerably state-owned oil firm Pemex and the Federal Electricity Commission (CFE) (see MEXICO: Expropriation risk may rise as AMLO term ends – May 24, 2024).

In his final year in office, AMLO has doubled down on his statist, nationalistic stance, seemingly seeking to cement a legacy of recovering economic sovereignty.

The judicial reform is one of his boldest moves to date (see MEXICO: Morena to pursue major constitutional change – September 6, 2024). AMLO argues that it is necessary to address corruption and that the popular election of judges will strengthen their ability to act independently. However, critics frame it as a vengeful attack on a judiciary which has, for years, blocked the advancement of legislation it has deemed unconstitutional, such as AMLO’s Electric Industry Law, which sought to favour the CFE above private-sector players.

The removal of members of the judicial branch — particularly the Supreme Court — risks undermining checks and balances on the government’s actions and heightening concerns over the security of investments in Mexico.

New FDI plunge

Talk of major reforms during campaigning ahead of the June 2 general election may help to explain a sharp drop in fresh FDI during the first half of 2024. While the reinvestment of profits and transfers between companies of the same group maintained their usual rhythm, new FDI during the first quarter fell to USD644.9mn — an amount below that recorded when the pandemic hit the global economy in the second quarter of 2020 (USD799.4mn).

During the second quarter it fell further, reaching only USD264.4mn — the lowest number since the third quarter of 2013. The amount of new FDI accumulated in the year leading up to the second quarter of 2024 was USD3.0bn — the lowest amount since 1993, before the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

With the downward trend in new FDI evident from early 2023, the recent numbers are far less likely to be a fluke than an indicator of a loss of investor confidence in Mexico.

More constitutional changes

Proposals by AMLO to remove several autonomous bodies and regulators may — as intended — save the government money that it can put towards social programmes and pensions. However, they risk further eroding confidence in Mexico as an investment destination.

AMLO has argued that the work done by such bodies would be undertaken by government ministries. However, with the plans also implying the elimination of regulators tasked with ensuring a level playing field for all competitors, that would seemingly see the government acting simultaneously as both an interested party and as a judge: a prospect that raises particular concern among players in the electricity and oil sectors, given the government’s recent attempts to strengthen Pemex and the CFE (see MEXICO: Morena to pursue major constitutional change – September 6, 2024).

Under AMLO’s plans, the Federal Economic Competition Commission (charged with fighting companies with excessive market dominance and promoting competition) and the National Institute for Transparency, Access to Information and Personal Data Protection (which allows the public to demand information on government decisions and contracts) would also be abolished. While the main impact of removing the latter would be domestic, the removal of the former is likely to concern foreign investors deeply.

AMLO’s usual reply to assertions that the constitutional changes may damage Mexico’s reputation and attractiveness as an investment destination is to claim that justice is above the markets and that investors should welcome the elimination of corruption and the budget savings achieved.