Russia’s oil industry has proven resilient despite being targeted by Western sanctions

Russian oil production fell by just over 4% in 2025 due to the commitments made under OPEC+ production agreements. Total crude and liquids production averaged 10.2 million barrels per day (b/d). Although output fell, crude exports rose by just under 0.5%. However, product exports fell by almost 8%, meaning that overall oil exports fell by just over 3%. Nevertheless, this was 1.5% higher than the last pre-war year in 2021.

What’s next

Subsidiary Impacts

- Russia’s ‘shadow’ oil tanker fleet will continue adapting to G7 measures to prevent oil from being sold above the ‘price cap.’

- Improved relations with the United States could cause Washington to relax measures targeting Russia’s oil industry.

- Oil-related federal tax revenues are likely to be slightly lower than in 2024.

Analysis

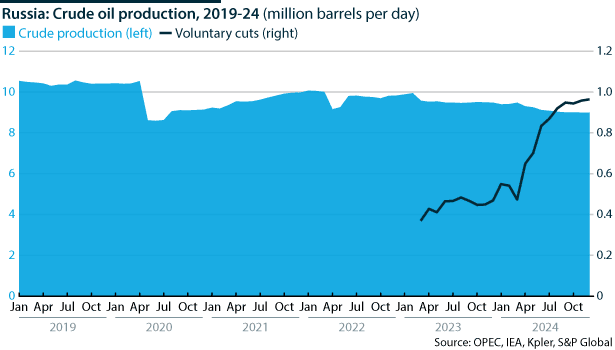

Russia’s crude production has declined modestly over the past two years. Between early 2023 and late 2024, output fell by over 400,000 b/d, from 9.57 million b/d to 9.17 million b/d — a 4% drop. A further 1.0 million b/d of condensate was produced, yielding a total liquids output of 10.2 million b/d.

The drop in production was largely driven by Russia’s commitment to OPEC+ production cuts, which were implemented in 2023 and 2024 to stabilise global oil prices (see INT: Oil surplus hits prices and clouds OPEC+ plan – December 27, 2024). By the end of 2024, Russia’s pledged reductions had reached nearly 1 million b/d. While sanctions and technical challenges have also eroded production capacity, these formal output constraints accelerated the decline.

The shifting landscape of Russian oil exports

Despite the fall in crude production, Russian oil exports have remained resilient. In 2024, total crude exports increased marginally by 0.5%, reaching 3.49 million b/d.

87%

China and India’s share of Russian crude oil exports in 2024

India and China consolidated their dominance as Russia’s top customers, collectively accounting for nearly 87% of its crude exports, with Turkey emerging as the largest European buyer.

However, oil product exports have not fared as well. Total exports of refined products declined by almost 8% to 2.45 million b/d in 2024. While Turkey remains a key customer, Russia has expanded its oil product sales across Asia, Latin America and North Africa, capitalising on demand from buyers seeking discounted energy.

US policy initiatives risk strengthening China’s influence in Latin America

Despite this drop in refined product exports, Russia’s total oil exports in 2024 amounted to 5.94 million b/d, a 3% decline from the previous year. This figure still exceeds pre-war levels in 2021 (5.85 million b/d).

Crucially, oil revenues have also held firm. The IEA estimates that Russian oil export revenues climbed by 2% in 2024 to USD192bn, driven by both OPEC+ market stabilisation and Russia’s success in skirting price caps.

Moscow has increasingly relied on a “grey” tanker fleet and intermediaries willing to facilitate oil sales at prices above the G7-imposed limits of USD60 per barrel (/b) for crude and USD100/b for refined products (see RUSSIA: ‘Shadow fleet’ will prove resilient – December 16, 2024).

The diminishing impact of the price cap

When the G7 imposed the price cap in December 2023, many expected it to curb Russian oil revenues substantially. However, Russia has largely managed to sell its crude above the cap, albeit at a significant discount to Brent. Russia’s benchmark crude, Urals blend, initially traded at an average discount of USD16.36/b to Brent in early 2024, but this narrowed to USD11.99/b in the second half of the year.

A shadow fleet of tankers, the use of non-Western insurers, and a growing number of trading intermediaries outside Western jurisdictions have made circumvention of the cap possible. This network has allowed Russian crude to flow freely despite nominal restrictions. However, this system has come under renewed pressure following a late-2024 escalation in US sanctions (see RUSSIA: New US oil sanctions will impose costs – January 20, 2025).

The Biden administration’s late-stage crackdown

As President Joe Biden’s term drew to a close, his administration sought to cement its legacy of supporting Ukraine by tightening the screws on Russia’s oil sector. New sanctions, imposed in December 2024, marked a significant escalation.

For the first time, Washington directly targeted major Russian oil firms, sanctioning Surgutneftegaz and GazpromNeft — Russia’s third- and fourth-largest producers. Additionally, 183 tankers linked to Russian oil shipments were blacklisted, accounting for roughly one-third of Russia’s estimated grey fleet.

Recent US sanctions caused significant disruption to Russian oil exports

These measures have already disrupted trade flows. While a grace period until late February 2025 was granted to allow in-transit shipments to be completed, sales of Urals blend for March delivery have stalled. Even buyers in India and China — Russia’s most steadfast customers — have hesitated to violate US sanctions outright.

Furthermore, the effective removal of numerous tankers from circulation (due to problems with port access, maintenance, ship-to-ship transfers and revenue losses as a result of their blacklisting) has driven up freight costs. Within days of the sanctions announcement, VLCC (Very Large Crude Carrier) shipping rates spiked by 61%, making Russian crude less competitive.

Concurrently, the sanctioning of two Russian insurers — Ingosstrakh and Alfa Strakhovanie — has complicated matters, reducing the ability of tankers carrying Russian crude to secure adequate coverage. Several Chinese ports in northeastern China have already restricted entry to Russian-insured vessels, raising concerns that others may follow suit.

Structural challenges loom for Russian oil

There is increased questioning of the viability of Russia’s oil sector in the short term and beyond. Moscow-based analysts estimate that around 800,000 b/d of Russian crude exports are immediately at risk, equivalent to nearly one-quarter of the country’s December 2024 export total.

Meanwhile, domestic oil firms have begun sounding alarms over financial constraints. GazpromNeft, for instance, has renewed calls for a tax overhaul to preserve investment in production. The company advocates for a shift from Russia’s traditional revenue-based tax regime to a profit-oriented model — already in place for about half of the country’s output.

Rosneft, Russia’s largest producer, has also faced headwinds. The firm recently announced delays to its Vostok Oil project, a flagship Arctic development critical to future output (see RUSSIA: Vostok project will define Russia’s oil future – July 1, 2024). Originally slated to begin production in 2025, Rosneft has now pushed back the launch to 2026.

Rosneft CEO Igor Sechin cited “global oil market dynamics” and the fact that the project’s key pipeline is only one-third finished. Given that Vostok Oil is intended to offset natural declines elsewhere, even a modest delay raises concerns about Russia’s long-term production outlook.

The Russian government remains publicly optimistic. The latest draft of the country’s energy strategy, covering the period to 2050, projects that Russian liquids production can be maintained at 10.8 million b/d for the next two decades — assuming the unwinding of OPEC+ production cuts. However, given the increasing challenges posed by sanctions, technical constraints and investment bottlenecks, even the most optimistic figures within the Russian oil sector must now question whether this target is achievable.

The Trump wildcard

US President Donald Trump’s policy toward Russia and the oil industry is a crucial variable in Russia’s energy outlook.

Trump may see the removal of oil-related sanctions as a bargaining chip in negotiations with Moscow, especially since reintroducing Russian oil to global markets would help him fulfil another key campaign promise — lowering energy prices for US consumers.

However, Trump may also tighten sanctions further if he feels the need to exert pressure on Russia.