Budgeting for the fiscal year that began in most states last month shows a sharp drop in spending from recent years

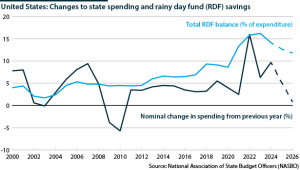

Most states have now completed their budgeting process for fiscal year (FY) 2026, which for many began on July 1. As states are unable to run deficits, preparations for each fiscal year’s budget use macroeconomic projections to ensure that planned outlays will correspond to expected revenues. For the coming year, state budgets are largely flat, with an overall increase in spending of only 0.8% nationally, compared to 5.1% for 2025 and 9.7% in 2024.

What’s next

States may pass mid-year supplementary budgets if needed, although in most cases the current levels of reserve, or rainy day, funds should be enough to sustain operations. Investments could see further cuts, however, jeopardising long-term economic potential. A looming concern for many states will be the impact of cuts to federal spending on Medicaid and food assistance programmes as a result of the budget legislation passed by Congress last month.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Federal budget cuts are already slowing or halting some state transportation projects, which could slow future economic development.

- If federal data collection appears to be politicised, state data on revenue collections may become a valuable source of information.

- Florida, the state most reliant on sales tax revenue, may benefit if federal tariff policy feeds into higher prices and inflation.

Analysis

State and local governments together spend about USD4tn annually. Unlike companies or individuals, all states but Vermont have statutory requirements to produce balanced budgets in which spending on operations, although not pensions or capital projects, is tied to expected revenue. Although most have some degree of leeway for workarounds, this leaves these tiers of government very exposed to economic changes that reduce revenue from income and sales taxes, or from Washington, or both.

As revenue projections change each month, budget authors will adjust their planning for the next year. For example, Democratic Governor JB Pritzker of Illinois revised revenue projections down by USD500mn in May, a 1% reduction from his February number, removing much of the space for new spending priorities as deadlines loomed ahead of the start of the new fiscal year.

Two concerns for 2026

In planning for FY2026, states faced two main concerns.

Economic downturn

One was the possibility of an economic downturn, with data from the jobs market indicating a softening economy and the economic impact of the Trump administration’s tariffs and immigration policies as yet unclear. During the 2007-09 recession, total state tax revenue dropped by 17%, and the ensuing budget cuts were then blamed for extending that recession, acting as pro-cyclical austerity measures. State spending dropped by 3.8% in 2009 and 5.7% in 2010.

Any economic slowdown would come after years of steady revenue increases for states. Since 2000, the average year has seen an increase of 4.4% in total state spending, but since the pandemic that figure has increased to 7.9%.

States have been able to increase spending in recent years but FY2026 will be different

The National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO) projects an increase of 0.8% in state spending in FY2026, the lowest since the budget cuts in 2010. In most cases, the multi-year pandemic -related federal support that helped states meet spending needs resulting from COVID-19 is now exhausted, with reductions in capital spending being preferred to operational cuts.

Federal funding cuts

Cuts to federal funding are the other worry. Transfers from the federal government are 35% of total state revenue and were above 40% after the pandemic as the federal rescue packages, incorporating lessons from the recession a dozen years earlier, included significant support. However, states are now dealing with a White House that is looking to cut grants and transfers to states.

One result is that many infrastructure projects with joint state and federal funding, such as new highways, are put on hold while new feasibility studies are done to consider how, or whether, they can continue with lower funding levels.

A longer-term concern involves the cuts made to Medicaid, which provides healthcare to those on low incomes, by the federal budget bill passed last month. Although administered by the states, the programme is largely funded by Washington, which has now cut some 12% of its expected spending over the next decade (see UNITED STATES: OBBBA may aid Democrats next year – July 11, 2025).

States respond

Most states have responded to the changing situation by reducing overall outlays and relying on rainy day funds. These saving funds, which act as a buffer against any major economic downturn, have grown steadily since the recession, from a median of 1.8% of total expenditures for FY2011 to 12.9% for FY2026. Rainy day funds provide states with a cushion if they miss revenue targets and can also be used for one-time investments.

Some states have also been looking at new sources of revenue:

- Massachusetts passed a “millionaire’s tax” in 2022 that imposes an additional 4% surtax on the regular 5% income tax on residents with taxable incomes above USD1mn; in FY2025 it brought in about USD3bn.

- Last month, Illinois implemented a USD0.25 transaction fee for each wager made via online sports gambling sites. This is being passed on by the major sportsbook companies directly to customers.

- This year Rhode Island approved a new tax on vacation homes worth more than USD1mn. Popularly known as the “Taylor Swift tax” because the singer owns the state’s most expensive vacation home, from next year this will charge USD2.50 for each USD500 of assessed value above USD1mn.

Limited options

However, there is little countervailing action that governors and legislators can take to avoid a fiscal squeeze if an economic downturn occurs on top of cuts made by Washington. Suggestions of higher taxes will usually trigger fears of making the state uncompetitive, or of driving away wealthier residents.

State legislators remain very wary of higher taxes as a response to falling revenue

California released a revision to its current budget earlier this year that sought to cut USD5bn from Medi-Cal, the state’s Medicaid provider, and also proposed cuts to foster care and food assistance in FY2026. Given that this was proposed by Governor Gavin Newsom, who is clearly planning to run for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2028, it suggests the tight constraints under which states are working (see UNITED STATES: Federal funding needs limit governors – March 4, 2025).

Broader political impact

Much of the spending instigated by the Biden administration (2021-25), not least the Inflation Recovery Act (see UNITED STATES: Democrats may not benefit from IRA – November 14, 2023), flowed through projects instigated at the state level, with members of Congress, governors and state legislators all taking credit for local expenditure. Republican states often did better than Democratic ones from the Biden-era programmes as federal fundings allowed new infrastructure-related projects to commence.

If revenue drops, however, the state-level debate becomes about what and where to cut. This could potentially lead to a more general anti-incumbent environment across the country by the time of the November 2026 elections, as elected officials defend unpopular decisions. In particular, it may create some problems for governors seeking re-election. There will be gubernatorial elections in 36 states next year, whose current incumbents are split equally between the two parties with 18 each.