Under international pressure, Israeli and Hamas negotiators are today discussing details of the US Gaza peace proposal

Israeli and Palestinian Hamas negotiators today begin indirect talks in Egypt on the implementation of US President Donald Trump’s 20-point peace plan for Gaza, unveiled on September 29. The proposal, which aims to end nearly two years of war in Gaza, links an immediate ceasefire and a large-scale hostage/prisoner exchange to the longer-term establishment of a new, externally controlled transitional authority and progressive Israeli military withdrawal as Hamas disarms.

What’s next

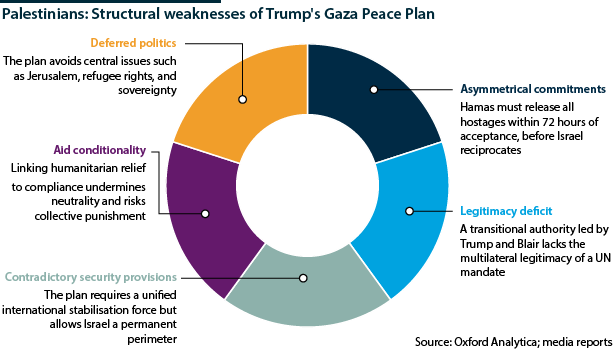

The talks could facilitate partial implementation of the plan: a limited ceasefire, selective releases and increased aid flows. The proposal will remain the basis for international discussions on the conflict. However, its broader design of external administration for Gaza and conditional Palestinian sovereignty will create tensions in the longer term, since it lacks legitimacy, rests on unrealistic conditions and leaves Israel with decisive veto power.

Subsidiary Impacts

- The undefined ‘pathway’ to Palestinian statehood will likely be postponed indefinitely, replicating the pattern seen after the Oslo talks.

- On top of the plan’s internal security contradictions, local Gaza militias armed by Israel could contribute to further fragmentation.

- Trump will focus on economic aspects and may revive his earlier ‘Gaza Riviera’ concept, but businesses will be extremely wary of investing.

- The results of Israel’s elections, which could come earlier than scheduled in 2026, will affect the plan’s longer-term prospects.

Analysis

The talks are launching under heavy pressure from Trump, who yesterday wrote on social media that the “first phase” should be completed this week, and appealed to all parties to “MOVE FAST”.

He has expressed optimism regarding the outcome — according to one report, excoriating Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu for excess negativity in an October 3 phone call. He has also issued dire threats of “MASSIVE BLOODSHED”, mostly directed at Hamas, if the parties delay.

Under Trump’s direction, the negotiations will likely defer the more difficult issues and focus on agreeing a full ceasefire to facilitate the logistics for Hamas to free all the living hostages taken on October 7, 2023, and to return the remains of those who have been killed. So far, Israel has reduced the strikes following demands from Trump but retained the right “to fire back for defensive purposes”, with further Palestinian deaths reported yesterday and today.

The sequencing of prisoner and hostage swaps obliges Hamas to release all hostages within 72 hours of Israel’s acceptance, and before Israel begins releasing Palestinian prisoners. These are to include 250 serving life sentences and more than 1,700 detained in Gaza over the past two years.

This sequencing places the burden of compliance entirely on Hamas, which will therefore likely attempt some delaying tactics in order to retain leverage on:

- naming the high-security prisoners to be released (which will in turn risk further pushback in Israel);

- speeding up the return of UN-administered international aid (see PALESTINIANS: Gaza can expect further aid crises – July 29, 2025); and

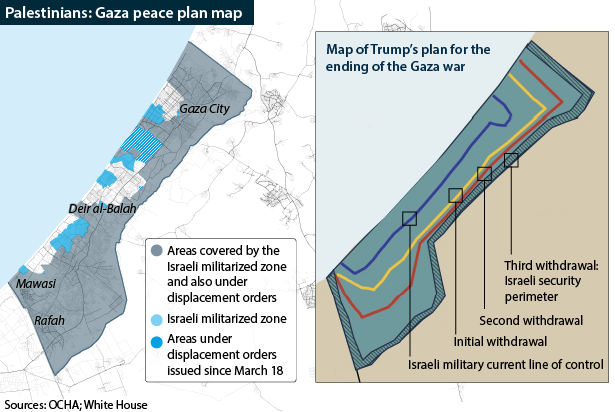

- pressing for the implementation of the first phase of Israel’s military withdrawal, as specified under the 20-point plan.

Political context

The fanfare around the plan has created some heavy momentum. Its announcement was staged as a high-profile joint event in Washington. Trump described the deal as “all or nothing” and gave Hamas “three or four days” to accept or face “a very sad end”. Netanyahu was given little choice but to back the plan publicly, highlighting the aspects aligned with Israel’s aims of releasing the hostages, dismantling Hamas and restoring security.

At Trump’s urging, Netanyahu also had to issue an apology to Qatar for the Israeli airstrike targeting Hamas in Doha that killed a Qatari security official, acknowledging the breach of Qatari sovereignty and pledging it would not recur (see QATAR: Peace plan will put pressure on Doha to deliver – October 2, 2025).

The episode illustrated both Trump’s leverage and Netanyahu’s need to maintain US support while managing a fractious coalition at home (see ISRAEL: Netanyahu may quietly backtrack on Gaza push – August 18, 2025). In addition, it could provide a credible basis to assure Hamas leaders abroad — or those later exiled from Gaza — of a degree of safety if they engage in the talks.

Nonetheless, in many respects the framing of the plan has left little space for negotiation. It cast Hamas as the primary obstacle, and the absence of Palestinian involvement reinforced its character as externally imposed rather than a negotiated settlement.

Drivers of support

Much of the momentum behind the plan comes from a rising global urgency to end a war that has killed more than 60,000 Palestinians and wounded over 145,000 since October 2023, according to Gaza’s health ministry, while displacing well over 1 million. Its appeal lies mainly in being the only framework on offer to address reconstruction, security and governance, though its capacity to do so is limited (see PALESTINIANS: Gaza may face long-term controlled chaos – July 7, 2025).

Even so, the key external players seem to have agreed that this draft, simply because it is backed by Trump, presents the only opportunity to move forward. It has also shifted the incentives for the warring parties.

Trump and Israel

For Trump, presenting the plan as the all-or-nothing framework positions the United States as indispensable broker and allows him to claim leadership in ending the war. His orchestration of Netanyahu’s apology to Doha demonstrated his leverage and signalled to Arab partners that Washington would hold Israel accountable — strengthening his mediator role.

Overt pressure from Trump can help Netanyahu domestically

It also gave Netanyahu a degree of political cover with his far-right coalition partners, who criticised his apology to Qatar as weakness and prefer a longer conflict ending in Gaza’s settlement and annexation. Netanyahu has emphasised domestically that Israel alone will decide when threats are eliminated, and that despite the plan’s mention of Palestinian statehood aspirations, Israel will remain adamant in rejecting Palestinian sovereignty.

For mainstream Israeli society, the plan offers the return of hostages, formalises international oversight of demilitarisation and transfers humanitarian and reconstruction burdens outward, while providing a means to restore international legitimacy and reduce the economic, military and social costs imposed by the conflict. A long-term security perimeter also preserves Israeli veto power.

Earlier ceasefire attempts have struggled because of threats from the far right to leave the right-wing coalition and collapse Netanyahu’s government. However, the premier seems now to have decided that it is more important to retain Trump’s favour than maintain a government that would in any case have struggled to pass a budget by the March 2026 deadline, necessitating new elections. In any case, centrist parties have promised Netanyahu at least temporary political cover in the Knesset (parliament) to allow him to accept the deal.

Palestinians and Arabs

Under heavy pressure from external patrons, Hamas on October 3 accepted core elements of the plan, including hostage and prisoner releases, and agreed to negotiate on the rest. Its reticence to highlight the elements it rejects — particularly the externally imposed Gaza administration and the full disarmament of the movement — allowed Trump to frame this as agreement.

Arab and Muslim states are pushing Hamas to avoid alienating Trump

Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Jordan, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) have endorsed the plan, citing its commitment to non-displacement of Palestinians and a political horizon for a two-state solution. Their diplomatic and material support will be vital to deploying a stabilisation force and financing reconstruction.

The Palestinian Authority (PA), which controls the West Bank, has also expressed cautious endorsement, describing Trump’s initiative as sincere and signalling a willingness to engage regionally. After years of PA exclusion from Gaza, even a distant, conditional prospect of return is attractive. The PA’s caution likely reflects an awareness that re-entry might restore relevance but would also generate dependency (see PALESTINIANS: Reform failures weaken state prospect – September 10, 2025). However, the PA has few options given the need for US and Arab state backing — and may in any case assess that implementation of the later stages of the plan remains unlikely.

Subsequent phases

This confluence of interests could well push through the initial ceasefire and hostage/prisoner releases. However, subsequent progress is more uncertain, depending on whether the current level of international interest, especially from Trump, is sustained over a longer period.

Under the plan, the next step would be to establish the Gaza International Transitional Authority (GITA), to be overseen by an international ‘Board of Peace’ chaired by Trump and including such figures as former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair. Beneath this board, a technocratic Palestinian committee would manage service provision.

Meanwhile an International Stabilisation Force (ISF) composed of Arab and Muslim troops would maintain order and supervise disarmament (see EGYPT: US Gaza peace plan has major pitfalls for Cairo – October 3, 2025). Israel would begin phased redeployment but retain an indefinite “security perimeter” in and around Gaza until it judged the territory secure.

The financial design establishes a Grants and Finance Accountability Facility (GFAF) to reassure external donors that reconstruction funds will be properly managed. This system is designed to operate independently of Hamas, the PA and Israel, reassuring donors that their money will be used as intended. Previous Gaza reconstruction efforts, such as after 2014, faltered when donors withheld funds due to diversion risks and corruption concerns.

Hamas has strong objections to much of this longer-term plan, particularly the international oversight, disarmament and Israeli security veto. Its caution about openly rejecting them only defers the argument. Indeed, Hamas today on Telegram emphasised that reports stating it had agreed to hand over its weapons to an Egyptian-Palestinian authority under international supervision were misleading and aimed to sow confusion.

Hamas rejection would not necessarily destroy the deal

In practice, full Hamas acceptance of the longer-term aspects remains highly unlikely, with the effect of shifting responsibility for any resumption of the conflict onto the movement. Even so, the Trump plan allows for partial implementation in ‘terror-free areas’ handed over by Israel to the ISF, so aid and reconstruction could proceed even without Hamas’s consent.

A key indicator of whether Washington and other stakeholders are likely to remain committed to seek to push through the rest of the plan will be whether the ISF, GITA and GFAF are actually established, staffed and funded. Another is whether Trump takes a personal interest in his role chairing the ‘Board of Peace’.

Moreover, even in the scenario that the talks collapse during or after the initial phase, the Trump plan will remain the ‘only game in town’ for most stakeholders, and the basis for ongoing peacemaking efforts.

Legal frameworks

This means that the proposal’s structural weaknesses are likely to matter to the future of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

The GITA resembles past international administrations in Kosovo and East Timor, but it diverges in key respects: unlike those cases it lacks a UN mandate, it was drafted without local participation, and it is framed more as an ultimatum than a negotiated settlement. The lack of a UN mandate would mean low Palestinian cooperation and long-term instability on the ground, while internationally it would weaken recognition, reduce donor confidence and risk normalising conflict management outside international law.

The proposal also departs from earlier conflict-resolution frameworks. The Oslo Accords of the 1990s created the PA, transferring to it limited but immediate powers of self-rule. The 2003 ‘Roadmap for Peace’ aimed to establish a phased and reciprocal path to a Palestinian state under international supervision.

The September 2025 proposal abandons that logic: Gaza would be placed under foreign administration for years, with Palestinian governance resting on reforms that remain undefined (though Trump has pointed to his maximalist 2020 Vision, which includes not only elections, rule of law and anti-corruption measures but also curriculum reform, full security control and demilitarisation — distant prospects for a PA further delegitimised by Israeli actions in the West Bank). The political future is addressed only through a vague ‘pathway’ toward statehood.

Separately, by presenting commitments such as non-displacement, humanitarian access and bans on ethnic cleansing as negotiable terms within a proposal, the plan could be seen as treating binding legal duties as if they were political concessions. This approach risks normalising breaches of international law by implying that compliance depends on agreement rather than obligation.