The impact of the proposed 100% US tariff on imported chips would hurt the United States more than its competitors

US President Donald Trump has repeatedly said he is considering imposing a 100% tariff on imported semiconductors. The proposed measure is part of Washington’s bid to boost domestic chip production, reduce dependence on foreign supply chains and strengthen industries linked to national security — with likely exemptions for companies that invest in US-based manufacturing.

What’s next

The actual implementation of a blanket 100% tariff remains uncertain, but the repeated signaling is likely to pressure foreign firms to increase their US investments. Major companies producing electronic devices — the largest end-use of chips — are already exempt from the extra levies. Nevertheless, many US manufacturers continue to depend on imported chips for their production processes, and a substantial share of US imports consists of goods that contain semiconductors. As such, the policy, if implemented, could prove more harmful to US industries than to its competitors and trading partners.

Subsidiary Impacts

- For business, the policy may be immaterial for large corporations that already invest in the United States.

- The tariff policy could exacerbate domestic inflationary pressures.

- The higher inflation could restrain US private consumption, impacting the global economic prospects.

Analysis

The semiconductor industry is highly globalised, in part due to the zero or very low tariffs between countries over the past few decades.

However, Trump’s proposed 100% tariff on semiconductor chips, although intended to boost US manufacturing, could inadvertently put the United States in a less advantageous position in the existing international division of labour in chip fabrication, since relocating fabrication facilities to the United States is unlikely to be feasible for many multinational firms in the near future.

Impact on the global semiconductor industry

If imposed, the impact of the extra chip tariffs on the global semiconductor industry is likely to be limited.

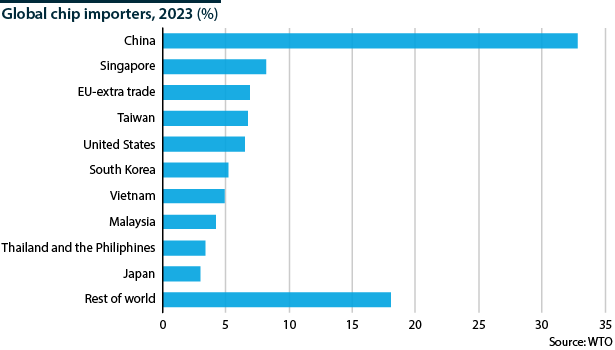

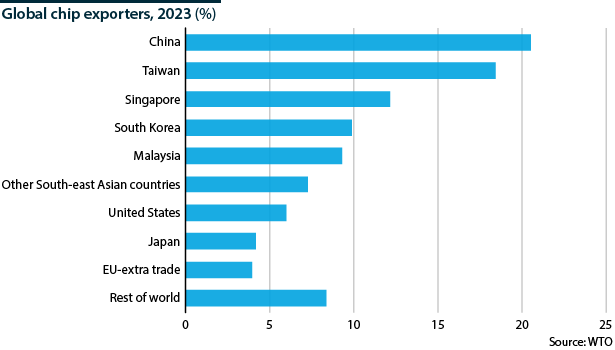

The United States is a relatively small player in the global semiconductor trade — countries in Asia accounted for nearly 70% of global chip imports and over 80% of chip exports in 2023. In comparison, the United States accounted for only 7% of global chip imports and 6% of global chip exports.

The well-established production network in Asia explains the region’s large share in the global trade of semiconductor chips. Often, incomplete chips are circulated among Asian countries during the fabrication process — for example, chips made in Taiwan could be sent to Malaysia for testing. Finished chips are then assembled — mainly in Vietnam and China — into final consumption goods (such as smartphones, tablets, computers, etc.) and exported from there to the global market, notably the United States.

China accounts for a significant share of global chip imports, as it is the key final assembly place for a variety of electronic devices entering global markets (see INT: China will stay key in legacy semiconductor trade – April 4, 2025). The country is also the leading producer and exporter of chips with low technology intensity (which are largely made by foreign firms in China), whereas Taiwan (mostly Taiwanese firms) predominantly makes and exports chips with high technology intensity (see INT: Geopolitical tensions test Taiwan chips industry – August 9, 2024).

Unlike Asian countries’ production networks in manufacturing chips, US involvement in the global semiconductor industry revolves around chip design — a segment that does not require frequent cross-border trade of either complete or partially fabricated chips.

Exemption clause

The Trump administration has promised to exempt several key chip-making companies from the extra levies as long as those companies relocate their chip fabrication plants to the United States.

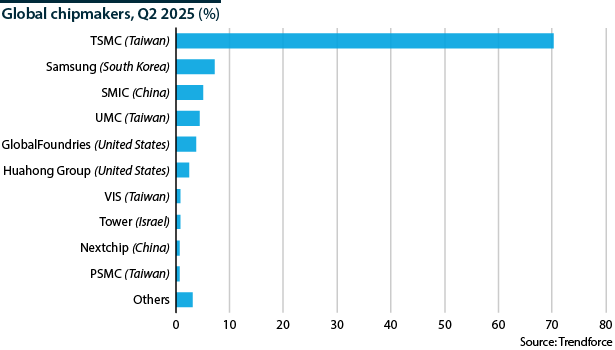

Major chipmakers such as TSMC, Samsung and GlobalFoundries have either already invested or committed to investing in the United States. Those three companies combined account for well over 80% of the global foundry business revenue. If their large shares in the global chip market are excluded from the new tariff, the impact of the proposed tariff on the global semiconductor business could be relatively small.

Impact on importing countries

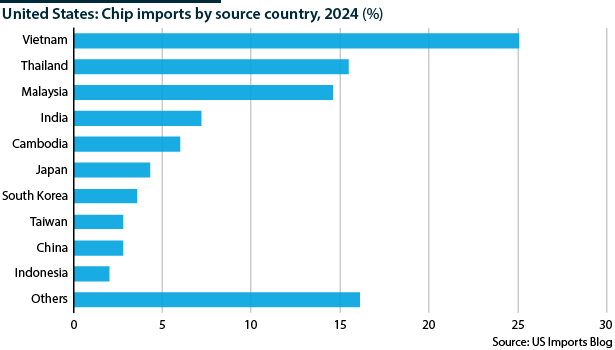

Vietnam (25%), Thailand (15%) and Malaysia (15%) are the main sources of US chip imports (see SOUTH-EAST ASIA: Region seeks strategic balance on AI – June 18, 2024). Overall, Asian countries accounted for 84% of total US chip imports.

84%

US chip imports from Asia

However, much of the chip trade between the United States and Asia involves intra-firm transactions — chips being sent back and forth by large semiconductor companies whose operations are expected to be exempt from the new tariffs.

Moreover, the Trump administration has promised to exclude smartphones, computers and other electronic products from the proposed semiconductor tariff. Since Asia — particularly China — serves as the world’s largest assembly hub for these devices, the exemption significantly reduces the potential economic impact on the region. Strategically, by sparing electronic devices from tariffs, the United States also limits its ability to use trade policy as a tool to weaken China’s broader manufacturing economy.

Impact on the United States

It is notable that the United States does not import large numbers of chips from the major chip-making exporters, such as Taiwan, South Korea and China, but instead does so from developing countries in South-east Asia, including Vietnam, Thailand and Malaysia.

The United States mostly imports chips from developing South-east Asian states

One explanation is that certain US semiconductor firms may fabricate chips at home (or proceed with one part of the fabrication process in the United States) before sending them to developing countries in South-east Asia for packaging — a stage that requires more labour and less technology intensity. These packaged chips are subsequently exported back to the United States. Depending on tariff regulations, these firms could either incur additional tariffs or avoid them if their US-based fabrication facilities qualify as tariff-exempt domestic investments.

The United States also relies on a variety of manufactured goods and industrial products from overseas that contain chips. In 2024, capital goods, automotive vehicles, engines and industrial supplies that might contain chips accounted for 64% of total US merchandise imports.

Consequently, higher tariffs on imported chips could harm domestic industries in the United States that rely on these chips to make their products, raising production costs. Extending tariffs to finished goods containing chips would likely also raise consumer prices and intensify existing inflationary pressures within the United States.