The two countries are striving to improve their relations after years of heightened border friction

Indian Foreign Minister S Jaishankar visited China last week. Last October, Delhi and Beijing agreed on an arrangement to end a border stand-off in the western Himalayas that began in May 2020. The heightened border friction was an impediment to India-China economic relations, which have grown to be substantial despite the strategic rivalry between the two. While two-way investment is modest, bilateral trade is heavily in China’s favour.

What’s next

Lingering mistrust will slow the pace of the reset in economic ties. Bolstering two-way investment will be challenging as each side negotiates for economic concessions, and India will struggle to reduce its trade deficit with China. Meanwhile, China’s close partnership with India’s enemy Pakistan and tensions linked to the Dalai Lama could undermine the rapprochement.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Both India and China will aim to maintain stability at their mutual border.

- India will increase its defence purchases and intensify efforts to expand domestic arms production.

- The suspended Russia-India-China trilateral dialogue will probably be revived.

Analysis

A Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) foreign ministers’ meeting in Tianjin was the pretext for Jaishankar’s July 14-15 visit — his first trip to China since 2019. Jaishankar’s other meetings during the two days included bilateral talks with Chinese counterpart Wang Yi in Beijing.

Last October, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping held their first formal talks since 2019 on the sidelines of the BRICS summit in Kazan, Russia (another SCO member).

The meeting followed the breakthrough on resolving the border stand-off, which spiked in June 2020, when violent confrontations occurred between Indian and Chinese troops in the Galwan valley. Both sides incurred fatalities during the clashes.

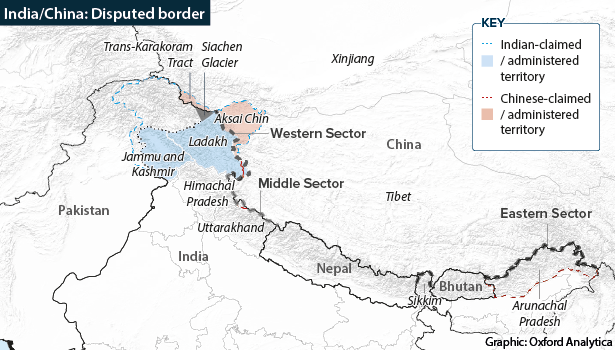

India and China have never formally demarcated their approximately 3,500-kilometre border.

Improving relationship

Jaishankar’s trip was a mark of the improvement in bilateral relations over the past nine months. According to the Indian Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) read-out of his meeting with Wang, the two ministers “took note of the recent progress made by the two sides to stabilise and rebuild ties”.

Following disengagement at the key friction points in the western sector of the border, the focus is now on de-escalation. Jaishankar urged “continued efforts” in this regard. In June, Indian Defence Minister Rajnath Singh called for a “permanent solution” to border demarcation when he met Chinese counterpart Dong Jun on the sidelines of an SCO defence ministers’ meeting in Qingdao.

Delhi recently called for a “permanent solution” to border demarcation

More broadly, the countries have sought to enhance people-to-people exchanges. China agreed to allow a resumption of the Kailash Manasarovar Yatra — an annual visit by Indian pilgrims to the sacred sites of Mount Kailash and Lake Manasarovar in Tibet. Both sides committed to restore direct flight connectivity, and India said today that it would resume issuing tourist visas for Chinese nationals.

Roadblocks on the economic front

Despite the more cordial diplomacy between the countries, boosting economic engagement will be difficult. During his meeting with Wang, Jaishankar raised what India sees as “restrictive trade measures and roadblocks to economic cooperation” (see INDIA/CHINA: Mistrust will endure despite key step – October 28, 2024).

USD99.2bn

India’s trade deficit with China in 2024/25

According to Indian Ministry of Commerce and Industry data, bilateral trade was worth USD127.7bn in India’s fiscal year ending March 2025, which meant that China was India’s second-largest trade partner, after the United States. However, India’s trade deficit with China increased to USD99.2bn from USD85.1bn in 2023/24.

Although India is generally eager to reduce its dependence on Chinese imports, one area where it is having to do so more speedily than it would prefer is rare-earth elements. In April, China announced export controls on seven rare earths and related magnets. The move notably hit production by some Indian automotive companies, and several such firms were frustrated as they sought approval from Beijing to procure rare-earth magnets.

At this month’s BRICS summit in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Modi said the group should “work together to make supply chains for critical minerals and technology secure and reliable”. He cautioned against any country using these resources for “its own selfish gain or as a weapon against others”.

Regarding investment, Indian official data have China as only the 23rd-largest source of India’s foreign direct investment (FDI) equity inflows between April 2000 and March 2025, accounting for inflows of about USD2.5bn. This was only around 0.3% of the total.

China data indicate that Indian FDI in China is even more modest.

Delhi’s investment policy is a key barrier to Chinese FDI in India. In April 2020, India made seeking government approval mandatory for FDI from countries with which it shares a land border. In most sectors, this investment used to flow automatically, except in the case of Pakistan and Bangladesh.

The NITI Aayog — an Indian government think-tank tasked with bolstering economic development — now appears to favour easing curbs on Chinese investment by allowing up to 24% Chinese ownership of an Indian company without the need for government approval.

Other thorny issues

The China-Pakistan ‘all-weather strategic cooperative partnership’ and contention regarding the Dalai Lama will add to the difficulty of resetting India-China economic ties.

China-Pakistan relations

During the May 7-10 military confrontation between India and Pakistan, when the neighbours came to the brink of a full-blown conflict, Pakistan relied considerably on Chinese military equipment. Pakistan notably claimed major successes yielded by Chinese-made J-10 fighter aircraft (see INDIA/PAKISTAN: Risk of hostilities will endure – May 14, 2025).

China is Pakistan’s top arms supplier.

Moreover, in early July, Indian Deputy Chief of Army Staff Rahul Singh claimed that China supported Pakistan amid the hostilities with “live inputs” on Indian positions. Pakistan and China both denied this.

The China-Pakistan partnership may constrain Indian engagement with the SCO (of which Pakistan is also a member). For example, at the SCO defence ministers’ meeting in June, Delhi refused to sign the drafted joint statement because it made no mention of the April terrorist attack in Indian-administered Kashmir that led to India’s strikes against Pakistan on May 7. India blamed Pakistan for the attack — even though Islamabad denied involvement — and launched the strikes in retaliation.

Dalai Lama

The succession of the Dalai Lama — the key Tibetan Buddhist leader who serves as an important figurehead for the Tibetan government-in-exile in India’s Himachal Pradesh state — could be an increasing point of contention between Delhi and Beijing.

The Dalai Lama turned 90 this month. In the lead-up to his birthday, he affirmed that the institution of the Dalai Lama would continue after his death and that the authority to recognise his successor would “rest exclusively with members of the Gaden Phodrang Trust, the Office of His Holiness the Dalai Lama”.

Beijing — which sees him as a separatist — says his successor must secure its approval. The MEA, for its part, responded to queries about his statement by saying that it did not take “any position” on “matters concerning beliefs and practices of faith and religion”, but this was only after Indian Minority Affairs Minister Kiren Rijiju backed the Dalai Lama’s remarks.

Shortly before Jaishankar’s visit to China, the Chinese embassy in Delhi said Tibet-related matters were a “thorn” in India-China relations. However, from India’s point of view, China’s construction of a major dam in Tibet could be more of a problem than the Dalai Lama’s succession, given the potentially adverse impact on water flow into India.