Beyond speculation over a ceasefire, there are increasing questions over Gaza’s future administration

As the conflict in Gaza approaches the two-year mark, it may be reaching a critical juncture. Deaths and displacements have mounted further, basic needs are unmet and the aid system is critically contested. Israel’s government is under increased international and popular pressure, as is Hamas. However, there is no clear consensus on what might come next.

What’s next

Following the conflict, there are four broadly plausible scenarios: Israeli handover to a reformed Palestinian Authority; construction of a new Palestinian administration presenting a facade of autonomy; direct Israeli reoccupation (and possibly resettlement); or a controlled political vacuum, described as ‘strategic ungovernability’. Given the difficulties attached to the first three, the last is looking increasingly likely to emerge by default.

Subsidiary Impacts

- An ungoverned Gaza would have a heavy human cost for Palestinian residents.

- Failure over Gaza will further undermine international humanitarian norms.

- Israeli political manoeuvring ahead of elections likely in early 2026 will play an important role in decision-making.

- If casualties in Gaza continue to mount, pressure will grow for the EU to take a firmer stance.

- Developments in Gaza will be crucial for the long-term prospects of West Bank Palestinians.

Analysis

Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu is today meeting US President Donald Trump in the White House, to discuss the possibility of a ceasefire in Gaza. Indirect talks in Qatar between Israeli and Hamas negotiators on a US-backed proposal for a 60-day ceasefire and release of hostages resumed yesterday, after a long pause.

Significant differences remain between the two sides, and a truce would be only the first step. Nonetheless, pressure is increasing for a deal, given Trump’s desire for a high-profile peace announcement (and the removal of a blockage to his wider Middle East diplomacy), as well as growing international discomfort with the situation in Gaza.

Unsustainable situation

After almost two years of war, Gaza is in a state of intense and sustained humanitarian catastrophe. The health ministry reports that 57,000 Palestinians have been killed, while the first independent survey, reported in the journal Nature, estimates over 80,000 deaths.

Over 1.9 million people — around 90% of the population — have been forcibly displaced, many repeatedly. Basic infrastructure has collapsed, and essential needs such as healthcare, clean water and food are largely unmet. Humanitarian access remains severely restricted — and politically contested.

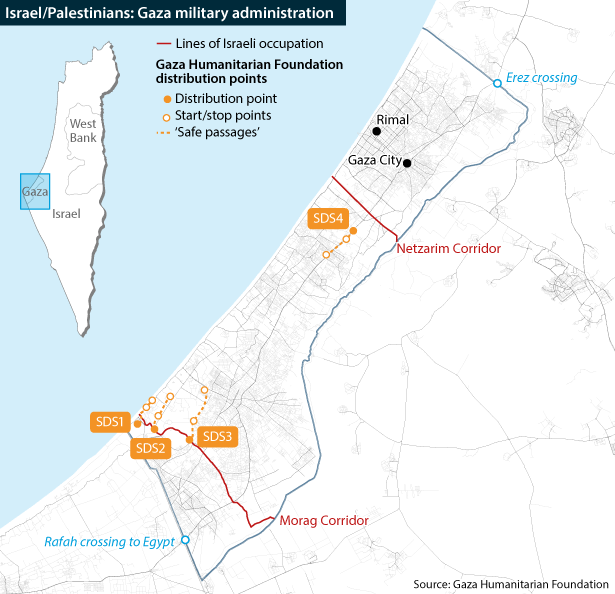

The Israeli army, which controls over three-quarters of Gaza’s territory, launched a new ground offensive in May, officially aimed at taking the whole territory (see ISRAEL: Gaza occupation would quell economic recovery – June 5, 2025). The new ‘Morag corridor’ aims to corral more of the population in the south.

Israel has also introduced a new approach to aid distribution. It is backing several large ‘mega-sites’, managed by the previously unknown Gaza Humanitarian Foundation (GHF), to control access to aid and bypass established UN-led channels, which Israel claims were diverted by Hamas. These have become a focus of daily violence, killing hundreds of aid-seekers.

Pressure to solve the Gaza problem is mounting

The humanitarian crisis has strained Israel’s relationships with key allies, including in Europe — even though some of the immediate pressure was reduced by the diversion of international attention to the Iran conflict (see EU: Robust action against Israel is unlikely – July 4, 2025). The United States remains broadly supportive, but Trump is increasingly eager to end the conflict to pursue wider regional plans. The Israeli public is also becoming more dissatisfied with the costs of the war.

Similarly, Hamas is under pressure from its foreign interlocutors (as well as the suffering Gaza population), although it is still pushing for a full end to the war. It has publicly stated that it would step down from governing Gaza in the longer term.

As the momentum to end the war mounts, though, there is still huge uncertainty over what might come next for Gaza, if a ceasefire holds and attention turns to the next steps. Broadly, four plausible scenarios are emerging.

Reformed Palestinian Authority

One possibility would be the reintroduction of the West Bank-based Palestinian Authority (PA) into Gaza under a revised mandate (see PALESTINIANS: Factions have no political path forward – March 20, 2025). This would involve institutional reform, international financial backing and renewed security cooperation with external patrons such as the EU, United Kingdom and United States.

It would resemble the model applied in the West Bank in the early 2000s. At that time, the PA, under non-ideological leadership and depending heavily on foreign aid, pursued technocratic institution-building as well as security coordination with Israel and Western partners.

This model was problematic, however, in that less than half of the promised aid came through. More importantly, the PA itself developed a persistent legitimacy deficit, exacerbated by the indefinite suspension of elections, lack of progress towards a Palestinian state and public perceptions of corruption — contributing to the empowerment of Hamas in Gaza (see PALESTINIANS/ISRAEL: Hamas Gaza war has deep roots – May 22, 2024).

Key international actors, including the EU and Gulf Arab states, tend to favour this prospect, as it involves a known partner, and links governance and reconstruction to renewed negotiations towards a two-state solution. Yet the obstacles are considerable: local distrust of the PA in Gaza, Israeli unwillingness, and acute donor fatigue in light of the sheer scale of reconstruction needed. Under current conditions, it remains implausible.

Facade of autonomy

An alternative, therefore, could be the establishment of a nominal Palestinian government in Gaza that rivals or replaces the PA. It would formally manage civil affairs in Gaza, but it would likely have to function under Israeli oversight, serving primarily to deflect international pressure. It would thus hold even less genuine authority or independence than the PA.

Evidence is emerging that Israel is supporting alternative Palestinian actors to distribute aid, assist the GHF and exert control in parts of Gaza, bypassing Hamas and established international mechanisms. The best-known is the clan-based militia led by Yasser Abu Shabab, whom Hamas has called to trial for treason.

The Israeli Ynet news site also reported on July 2 that two other militias armed and assisted by Israel were operating in the towns of Shujaiya and Khan Younis, respectively. It claimed that these groups were also affiliated with the PA — although one of the leaders named strongly denied both connections.

There are some recent local precedents for this model:

- In the 1970s in the West Bank, Israel supported the ‘Village Leagues’ as a putative alternative to the PA’s Palestine Liberation Organization. It aimed to create a compliant local leadership, but the plan ultimately failed due to lack of public support.

- There are also some parallels with Israel’s prior approach of facilitating Qatari cash transfers to Hamas — estimated at USD30mn per month between 2018 and 2023 — as a means of weakening the PA by propping up its rival in Gaza.

However, such a scenario would likely prove unsustainable, failing to resolve the underlying political crisis. It would lack legitimacy; it would likely deter sustained international engagement (which would continue to focus on the PA); and it would provide a target for a renewed insurgency.

Direct Israeli reoccupation

If alternatives fail, Israel could establish full military and administrative control over the Gaza Strip — perhaps as a temporary security measure that morphs into an open-ended occupation. This would resemble the situation during 1967-2005 — but under much more hostile and degraded conditions.

In practice, this scenario would comprise a consistent military presence throughout Gaza, controlling infrastructure, security, resource distribution and administration through a civil authority. Israeli forces would likely patrol the streets and maintain public order.

Israel would be legally responsible for the welfare of the Palestinian population, under the Fourth Geneva Convention. Nonetheless, Palestinian political and civil rights would likely be heavily suppressed.

Indeed, the government of Israel could bow to pressure from right-wing parties (including from within Netanyahu’s Likud as well as far-right coalition members) to re-establish Jewish-only settlements in the territory, on the back of ‘voluntary’ Palestinian displacement.

Politicians in Israel are flirting with the idea of reoccupation

Israeli officials, including Netanyahu, have retained a degree of ambiguity about whether reoccupation of Gaza is or could become a goal. The promise to “stay” until it can no longer threaten Israel could certainly become open-ended. The premier’s enthusiastic endorsement of the ‘Trump Plan’ to resettle Gaza Palestinians elsewhere and rebuild better could also point in this direction.

There would almost certainly be international condemnation, particularly from the UN, EU member states and Arab countries. However, especially if the United States were to back Israel, this would likely have limited impact. Past precedent, including the expansion of settlements in the West Bank despite sustained international criticism, suggests that rhetorical opposition alone is unlikely to shift Israeli policy.

Nonetheless, the high economic costs — especially if, for example, the EU were to consider imposing sanctions, or Arab countries reversed the ‘normalisation’ trajectory — could render this option unattractive to Israel. Israeli withdrawal in 2005 was driven by multiple factors: not only the high security and economic costs of occupation, but also the increasing salinity of the land undermining agriculture. None of these costs will have diminished since.

‘Strategic ungovernability’

The final and most likely scenario, therefore, might be termed ‘strategic ungovernability’ — describing a deliberate or tolerated condition in which no governing authority is permitted to emerge as a method of entrenching the power of the occupying force.

Controlled chaos could be a cheaper means to contain the Gaza threat

If no administrative structure is allowed to function, and no credible pathway to political stability emerges, then the resulting vacuum of power could leave Gaza in a state of sustained disorder. The lack of any alternative authority could work to Israel’s advantage in this scenario, without the heavy costs and responsibilities of formal occupation.

Israel’s systematic destruction of infrastructure, targeting of civil institutions and refusal to accept the legitimacy of either existing Palestinian political factions or international actors such as the UN Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) are already beginning to create such an environment. If the status quo is sustained and becomes the ‘new normal’:

- international donors will be unwilling to invest;

- local actors will be unable to organise, for fear of reprisals from one quarter or other; and

- humanitarian relief will continue to be filtered through military channels.

Partial precedents for such a strategy might include the systematic displacement of the Rohingya in Myanmar without the provision of an alternative authority or path to return; the deliberate fragmentation of authority in contested regions by nationalist leaders among the Bosnian Serbs and Bosnian Croats in the 1990s; or Israel’s own 1982-2000 occupation of South Lebanon, when inability to establish a stable proxy government produced a long-term insurgency.

This is not a formal strategy, but rather a reversion to the default. As such, it needs no active administrative framework. Instead, it would be sustained by the continued denial (or failure) of political alternatives, and the maintenance of the existing security perimeter, which isolates Gaza from regional and global systems.

By avoiding formal annexation, Israel would limit the legal fallout and responsibility for outcomes. However, by tacitly encouraging fragmentation, it would also block internal political organisation, representation or compromise between factions.

The costs of such a policy would be absorbed by civilians and by the few humanitarian institutions that are capable of functioning in that environment, rather than an ‘occupying power’.

Outlook

All of these scenarios remain possible, and none is yet inevitable.

The standard post-conflict logic that shaped previous international responses is that war ends in negotiation, negotiation leads to reconstruction and reconstruction supports political stability. That would point to the return of the PA or a facade of autonomy — but this logic may have collapsed in Gaza’s case.

Meanwhile, the country’s rightward drift means internal Israeli politics is veering more in the direction of formal reoccupation. However, that would be highly expensive, diplomatically problematic and administratively burdensome to maintain.

It seems increasingly likely, therefore, that ‘strategic ungovernability’ may emerge as the default option, facilitated by Israeli and international inaction. It could be driven by a combination of:

- the overwhelming scale of the destruction in Gaza;

- Israeli unwillingness ever again to accept Gaza becoming a source of cross-border insecurity;

- the failures of the PA; and

- Israel’s rejection of any progress towards Palestinian autonomy, contributing to the lack of a peace process.

That scenario plausibly reflects the convergence of Israeli military dominance, Palestinian political deadlock and international diplomatic fatigue. It would represent a long-term grim prospect, though, for Gaza Palestinians.