The number of Greeks is expected to fall precipitously in the coming decades, burdening the economy and public coffers

Parliament last week passed a controversial labour law allowing for a voluntary 13-hour workday, triggering strikes and protests. The government argues the bill is necessary to counter labour shortages and Greece’s negative demographic trends. The 10.4-million-strong population is expected to contract by 1.5 million by 2050, slowing economic growth and straining public finances.

What’s next

The government is mostly focused on implementing stopgap measures to address short-term negative impacts of the crisis rather than on long-term solutions. Financial incentives to boost births and encourage the return of expatriates will clash with the rising cost of living and changing social values. The ruling New Democracy (ND) party is unlikely to change its position drastically on immigration, while an ageing population may even suit its electoral interests.

Subsidiary Impacts

- For business, population ageing will exacerbate labour shortages and hamper economic growth.

- A rising proportion of people above 65 could slow innovation and the adoption of new technologies.

- Population ageing will alter saving and consumption patterns, raising demand for goods and services tailored to an older demographic.

Analysis

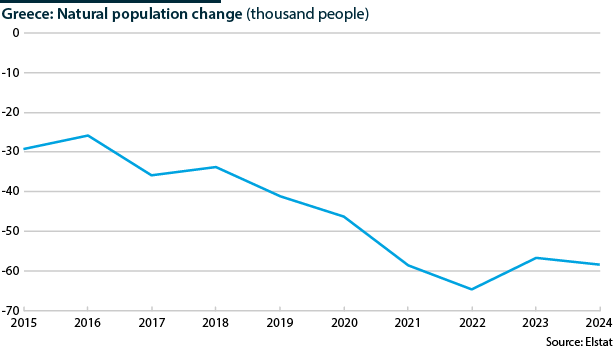

Greece is undergoing a severe demographic crisis. Signs first appeared in the late 1990s and early 2000s, when the natural growth of population (the number of births minus the number of deaths) fell close to zero (see EU: Mid-sized states will lose population unevenly – June 10, 2025).

The economic downturn in the late 2000s led to a sharp population decline caused by lower fertility. Greek statistical agency Elstat reports that the number of births plummeted from 115,000 in 2010 to just 69,000 in 2024, while the number of deaths rose from 109,000 to 127,000.

Migration flows

Net migration flows remained negative during this period, as Greece could no longer attract migrant labour and suffered ‘brain drain’ as Greeks emigrated abroad in search of employment. Moreover, immigration inflows included both economic migrants and asylum seekers, for whom Greece became a primary entry point to the EU.

Migration policy

The Greek government has taken a tough stance on migration. Hardliner Thanos Plevris was appointed migration minister in June, a move seen as appeasing the ND’s right wing (see GREECE: Ruling party may tack to the right – January 28, 2025). Shortly afterwards, he announced a complete revision of asylum policies and the introduction of new ‘disincentives’ intended to crack down on arrivals.

Government migration policy aims to address short-term labour market concerns

Yet the government also has to contend with the reality of labour market shortages. It has therefore introduced nine-month contracts to attract cheap migrant labourers, who will live and work in controlled environments such as farms and construction sites, having limited interaction with locals before returning to their homelands.

This will provide only a short-term boost to the domestic labour market, as the temporary workers will have no prospects of long-term residency or citizenship.

Unforeseen trends

The Greek population shrank by 720,000 in the aftermath of the post-2009 Greek economic crisis, from 11.1 million in 2010 to 10.4 million in 2024.

Such a trend was not foreseen by the Greek authorities. In 2007, Elstat forecasted that the population would total 11.5 million by 2050. By contrast, Eurostat projected a 2050 population of just 9 million, a difference amounting to 21%. Eurostat’s forecast to 2100 sees a further population decline after 2050, by 1.7 million — the third-largest decline in the EU as a percentage of total population, after Latvia and Lithuania.

Ageing population

Another aspect of Greece’s negative demographic trend is an ageing population.

People of pensionable age (65 years and older) totalled 23.3% of the population in 2024, up from just 14.5% in 2001. Their share is expected to rise further in the coming decades, peaking at 36% in 2055. This will exert progressively stronger pressure on both the labour market and public finances.

The Greek government appears unprepared to meet this challenge. Reforms that were implemented since the onset of the Greek sovereign debt crisis aimed to improve fiscal sustainability rather than strengthen the social safety net for the ageing population.

Pension reform, implemented by the government over the last few years, included the largest cut in pension provision in the EU. The European Commission reports that gross public pension expenditure in Greece will drop by 2.5% of GDP by 2070.

Elderly care

The total cost of ageing is relatively high in Greece, at 23.4% of GDP in 2022, according to the Commission’s 2024 Ageing Report. This includes expenditure on pensions, healthcare, education and long-term care. Despite expected sharp increases in the number of elderly citizens, public expenditure on their care will actually decrease to 21.0% of GDP by 2070.

This policy stands in contrast to support offered by governments in other euro-area countries experiencing similar demographic trends. Average age-related expenditure in the euro-area is expected to rise from 25.1% of GDP in 2022 to 26.5% in 2070.

In Greece, elderly care has traditionally been undertaken by family members. Yet socio-economic changes are expected to limit the provision of informal care in the future, shifting responsibility — at least partially — to the state. Factors curbing the provision of informal care include:

- rising costs of living;

- higher participation of women in the labour force;

- erosion of the family as a social institution;

- declining proportion of the working-age population; and

- pension reform.

Government policy

Despite a return to economic growth over the last few years (see GREECE: Risks remain for country’s economic recovery – July 31, 2025), financial, social and lifestyle factors continue to depress fertility rates. One such factor is the ongoing atomisation of Greek society. In 2009-24, the number of marriages and civil partnerships dropped from 59,000 to 51,000, while the number of divorces rose from 14,000 to 16,000.

The government is trying to reverse this trend with the Greek National Demographic Action Plan, announced in late 2024. The plan has a ten-year implementation horizon (2025-35) and encompasses over 100 measures. Its estimated cost is EUR20bn (USD23bn), to be financed from the Greek budget and EU funds.

The new labour bill may prove counterproductive

Among other policy measures introduced by the Greek government to counteract the negative impacts of the demographic decline is the adoption of the controversial labour bill legalising a 13-hour workday. The new legislation offers more flexibility to employers but has high potential to undermine workers’ rights. Placing additional burdens on the working population could backfire, causing rapid health deterioration, even lower birth rates and less provision of informal care for the elderly.

Brain drain

Some 650,000 (mostly young) Greeks left the country between 2010 and 2021. This brain drain peaked during 2013-16.

Greece cannot provide a sufficient number of high-quality, well-paying jobs to entice the return of its young people, so the government has resorted to tax discounts in order to encourage returns (see GREECE: Tax breaks may offer short-term relief – September 15, 2025). According to government estimates, around 340,000 Greeks (or half of the total) have returned to their homeland; the government’s goal is to attract another 50,000 young professionals by 2027.

However, tax discounts of the sort advanced by the government seem to have contributed little to decisions to repatriate. Most of the returnees cite personal or family reasons, according to a 2024 survey by the National Documentation Centre (EKT).

Political calculations

The voting population is ageing, and older voters are now overrepresented in elections. This trend is amplified by the rising political apathy of younger generations. Older people are generally more conservative and tend to gravitate towards the political establishment.

An ageing population may thus help ND expand its electoral base further, discouraging swift government action to address the demographic crisis.