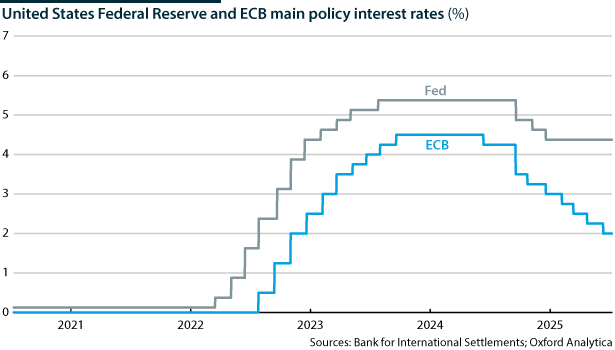

EU interest rates have halved in one year, but US rates have not matched them, due to higher inflation and tariff risks

The ECB is expected to hold interest rates at its meeting on July 24, having delivered 25 basis point (bp) cuts in February, March, April and June. The ECB main rate now stands at 2.15%, down from its 4.5% peak, whereas the US Federal Reserve (Fed) rate is stuck at 4.25-4.50%, just 100 bp lower than peak, due to persistent concerns over tariff-induced inflation.

What’s next

A tariff truce would clear the way for the Fed to deliver further rate cuts, as concerns over inflation would give way to fears of slowing economic activity and job-market softness. However, if both blocs apply tariffs of 20% or higher on each other’s goods, that would have damaging effects on inflation and GDP growth, complicating the decision-making of both central banks.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Political interference ahead of the 2026 Fed chair appointment risks making US policy less data-driven, increasing wider economic risks.

- Euro strength will hit Europe’s export competitiveness, exacerbating the pressures on the already fragile externally-driven growth model.

- Investor unease over US policy may aid the euro’s global standing, especially if the EU banking and capital markets unions make progress.

Analysis

Following a period when their monetary policies largely aligned, ECB and Fed policies have diverged over the last year. In June 2024, the ECB cut its benchmark rate of 4.50% by 25 bp. One year later, the latest 25-bp reduction brought the benchmark rate to 2.15%. ECB President Christine Lagarde indicated there was limited scope for further cuts.

The Fed started 2024 with a main rate of 5.25-5.50%; it reduced this by a cumulative 100 bp in the second half of the year. However, since President Donald Trump began his second term in January, and started to enact tariff hikes that threatened to reignite US inflation, the Fed has declined to deliver further rate cuts.

The benchmark ECB policy interest rate is less than half the Fed Funds rate

This has created a divergence between the two central banks. It has also stoked tensions between Trump and Fed Chair Jerome Powell, which risk unnerving markets and hence making the Fed even more cautious about inflation risks.

Inflation, jobs and growth

Policy-relevant data paint a nuanced picture in the euro-area and the United States.

In June, euro-area inflation was 2.0%, from 2.2% in April. US inflation rose to 2.7% in June. Labour markets on both sides of the Atlantic show modest strength overall, with unemployment at 6.3% in the euro-area and 4.1% in the United States.

Since 2023, unemployment has fallen in southern euro-area members, such as Spain, Italy and Greece, but risen moderately in northern members, including Germany and the Netherlands. This year the divergence has moderated, making the ECB’s job easier.

The US economy added 147,000 non-farm jobs in June, above expectations, but the strength was limited by sector. Leisure and hospitality expanded, as did private education and healthcare.

However, sectors including manufacturing, construction and financial and business services performed less well. Stricter immigration policy and deportations will gradually tighten the labour market, bolstering the argument for US monetary easing.

However, the Fed is alert to import-driven inflation pressures stemming from higher tariffs. Early evidence of tariff-related price pressures was seen in higher prices of toys, clothes and household and electrical appliances in June.

There are some arguments for futher easing by the ECB. The euro-area’s recovery remains fragile, especially in export-oriented industries, as frontloading of orders ahead of higher US tariffs markedly bolstered trade flows in the first half of 2025 (see EU: Recovery may falter as uncertainty chills activity – June 16, 2025). This portends weaker activity in the second half of the year.

Tariff policy uncertainty

The volatility surrounding US tariff policy makes it challenging to gauge its full implications for inflation, growth and labour markets, not only in the United States but also in Europe (see INT: Broad uncertainties will chill the global economy – July 14, 2025).

If US inflation peaks at 3.0-3.5% and then starts to ease in the fourth quarter, the Fed could cut rates in December. If not, rates are likely to stay on hold and the tensions between Trump and Powell will ratchet upwards.

A blanket duty applied to nearly every imported good would act as a tax on imports to the United States, raising domestic producer costs. This would strengthen inflationary pressures — although if it also damaged demand and employment, that would be an argument for the Fed to ease policy.

The ECB’s immediate concerns are more straightforward: US tariffs threaten EU exporters, a key engine of growth. The strong euro compounds the decline of their price competitiveness in the US market. This raises the threat to economic growth and could justify further rate cuts, especially if tariff-driven trade shocks far outweigh inflation concerns — although the ECB has limited scope, given where its policy rate now stands.

Medium-term

Absent a major shock, EU interest rates are unlikely to change much next year. The US outlook is far less certain.

Global tariff fallouts could drive Fed-ECB monetary policy convergence

ECB officials — in particular, Executive Board Member Isabel Schnabel — note that the trade conflict is a global shock, impacting both demand and supply.

A ‘zero-for-zero’ tariff arrangement between Washington and Brussels could relieve supply chain bottlenecks, reduce inflation pressures and justify Fed easing. In this scenario, the Fed might cut rates faster than the ECB, albeit from a higher starting rate.

However, the scenario is unlikely. The main question is whether the EU accepts an asymmetric deal, in which it keeps its import tariffs largely unchanged while accepting a general US tariff of 10%, or whether tariffs in both blocs rise to higher levels, with greater destructive impacts on consumption that also fuel inflation.

Elevated uncertainty

Trump’s expansive vision of how tariffs can be used and what they can accomplish creates challenges for how the ECB and Fed pursue their mandates. The Fed may need to consider how to factor in tariff-driven inflation spikes that could emerge or disappear based on bilateral negotiations. Currently, the Fed’s standby approach contrasts with market expectations, which still price in 25-50 bps of rate cuts by year-end, reflecting the pervasive uncertainty.

A recent New York Fed Survey of Consumer Expectations showed one-year-ahead inflation expectations at 3%, exceeding the central bank’s target by a large margin, which suggests that sentiment has not fully stabilised.

The ECB, meanwhile, must contend with constant shifts over European exporters’ access to the US market. US rate cuts threaten to strengthen the euro further, increasing the damage to EU firms’ competitveness in the United States.

The Fed and the ECB both review their strategy, tools and communications approximately every five years, and both are conducting reviews this year. The Fed last concluded such a review in August 2020; the ECB in July 2021.

The ECB finalised its new review in late June, at its annual central bankers’ conference in Portugal, stating that it saw no need to revisit the core pillars of its mandate.

The Fed intends to announce the results of its own review this summer. The annual central bankers’ forum in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, in late August, could give the first indication of any alterations. Larger changes could occur next year, as Trump will replace Powell by May 2026, when his term as chair ends.